By Sara Veltkamp, Minerva Strategies—

Words matter. The way we describe the challenges we’re addressing, the solutions we’re implementing, and the goals we’re trying to reach—it can all change how people perceive our work.

Words are also tricky, especially in cross-cultural situations. To be useful, they need to have meaning but we can’t always determine that meaning by checking a dictionary. Meaning can change with the context and cultural moment in which the words are being used. For example, a woman saying “me too” in 2012 would have meant she was piling onto a popular sentiment. Now, it has a very different implication.

Last week, I attended the Global Health Landscape Symposium organized by the Global Health Council (GHC)—an organization that supports and connects advocates and implementers around health priorities worldwide. The event was set against a backdrop of declining support and resources for global health in the US. Advocates are being forced to, as GHC President and Executive Director Loyce Pace wrote in her welcome letter, “Hold the line and play defense instead of working to advance bigger, bolder goals.”

Our discussions were far from holding the line. The panels and keynotes were powerful calls-to-action around shifting global health leadership from wealthy donor governments and INGOs to the governments and civil society in countries where the work is happening. USAID calls their efforts to this end “The Journey to Self-Reliance.”

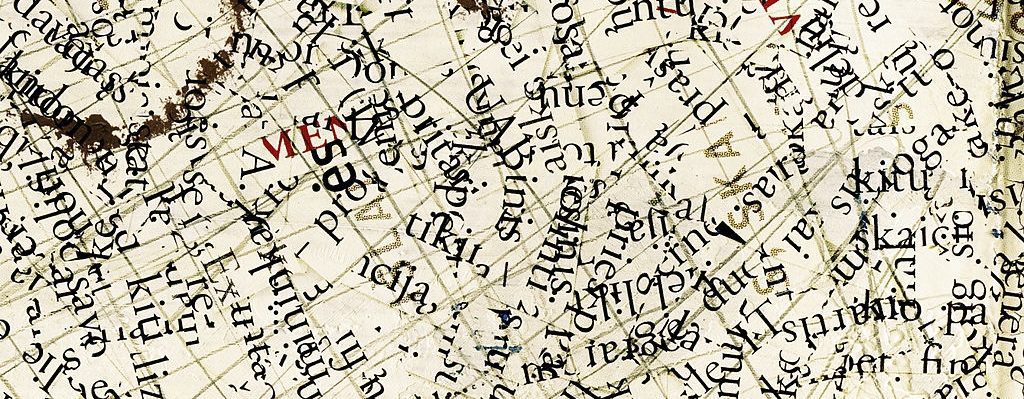

As a communicator, I particularly appreciated the focus on narratives we use to describe these efforts. The event kicked off with a community dialogue where participants were asked what challenges we face in shifting programs to local ownership models and what successes we can celebrate. We were asked to shout out words or phrases that best demonstrate these ideas and a word cloud was born.

According to the group, themes like colonialism, patriarchy, and top-down structures typified the challenges, but focusing on equality, shifting power, and effective indicators outlined the way forward.

How we talk about local ownership was a rich discussion throughout the day. In one session, we discussed why our US- or western-centric narratives could be problematic and what alternative words could be used to greater effect. We opened the discussion with how people in the room felt about the event theme, “Passing the Baton in Global Health,” a phrase that some felt was weighed down with power dynamic assumptions. The discussion of individual words and phrases folded into a larger conversation about shaping a narrative and who needs to be involved in that process.

At Minerva, a core part of our work with clients is often the development of a message framework that organizations can use as a shared internal document. Clients can draw from it to create materials and volunteers can use it to represent the organization with carefully chosen words. A message framework keeps an organization’s communications consistent and, as a result, more powerful.

As helpful as that document can be, the process of developing it is equally valuable. Spending time thinking about the words we choose inevitably leads to pondering the perspectives of people we hope to affect with those words. It’s not a navel-gazing exercise where people try to out-wordsmith each other, but instead an exercise in empathy—attempting to understand where people are coming from and using language that works in their reality.

Words are a challenge for global health communicators who want to describe shifting power and responsibility. Take “self-reliance” as an example. Most Americans believe self-reliance is a good thing. Those who are not self-reliant are shamed for depending on “the state” or living in their parents’ basement. But not all cultures strive for self-reliance—or its cousin independence—in the same way as Americans do. In cultures where social and cohesion are primary, the idea of relying mainly on oneself is not something to strive for.

These shifts represent an opportunity for communicators as well. What if we saw the goal of developing a narrative around democratizing global health as a chance to bring together diverse groups from our organizations and share perspectives? For example, I would love to hear what an on-the-ground partner thinks about being called a “partner” when so often that language masks the power dynamic where their communities’ priorities come second to the donors’.

This process would be complex and it is improbable that we would ever come up with something that works for everyone, especially given the language differences and other factors—but maybe that’s not the point. Through talking about the words used to ensure others understand our work, we will have built a clearer understanding of each other. That is a worthy goal in and of itself.